7. Securing sustainable growth is the most essential task of the city

Progress has been made with securing sustainable growth in respect of many of the city’s services. Enrolment in early childhood education has increased, more and more children are sent to their local school, and the city has succeeded in delivering on its training guarantee. The land use planning targets set for housing have been achieved. The volume of housing production has increased and exceeded the target in 2020. The pursuit of a denser urban structure has progressed thanks to infill construction. The percentage of people who choose walking as their mode of transport has increased, the city-centre tramway network has been extended, and boulevardisation is progressing as planned. The city now has a new central library (Oodi), and the network of local libraries has also been improved. The biggest challenges at the moment relate to wellbeing, continuing segregation between neighbourhoods, and the development of the city centre. The coronavirus pandemic has forced the city to pay more attention to the social and psychological wellbeing of young people and the provision of extracurricular activities and other related services for youngsters. Restoring the appeal and vitality of the city centre after the pandemic is a major challenge and crucial for increasing both social and economic activity in the city. Employment-based immigration has decreased as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic has also prevented the achievement of the targets set for the percentages of people relying on public transport, their own cars and cycling.

Ensuring comprehensive economic, social and ecological sustainability is one of the growing city’s key goals. This is monitored and reported along with indicators, in sync with the planning rhythm of the city’s operations and finances.

Helsinki’s deprivation index, which measures the welfare gap between population groups and geographical areas, improved by almost 30 points between 2015 and 2019 (100 -> 70.2). The deprivation index takes into account homeless people living alone, alcohol abusers, people who consider themselves lonely, and long-term welfare recipients.

Helsinki’s deprivation index also improved compared to the national average between 2015 and 2019 (Finland = 100; Helsinki 236.2 –> 170.4).

The City Board adopted a set of performance indicators for the City Strategy in 2018 and revised them in 2019. The progress of the strategy relative to the indicators has been discussed in both operational and economic reports.

Helsinki aims to raise children’s enrolment in early childhood education. The funds for the verifiably successful positive discrimination –funding will be moderately increased and will also be targeted towards vocational training and upper secondary education. Each and every school in Helsinki should be good enough to make parents happy to choose their local school.

The goal is for every neighbourhood in the city to have attractive early learning and basic education services that follow naturally from each other. Enrolment in early childhood education increased from 90.4% in 2017 to 93% in 2020.

New day care centres opened between 2017 and 2020 added 4,040 places to the city’s early childhood education capacity. More than 700 new places are due to be added in 2021.

The percentage of children who are sent to their local school increased from 86% to 92.2% between 2017 and 2020. Special-needs children are more likely to stay in their local school than before; the percentage has risen from 66% to 75% during the strategic planning period.

A knowledge-based model of positive discrimination between neighbourhoods has been adopted in youth work.

Helsinki will strive to hold its position as a textbook example in Europe of how to prevent segregation. Consequently, Helsinki strives to enable equality and wellbeing in all districts.

The City Council ratified a new action plan for housing and land use on 11 November 2020. The aim is to provide at least 7,000 new homes every year through development and the repurposing of existing buildings, and to raise the target to at least 8,000 new homes each year from 2023 onwards. At least 700,000 square metres of residential floor space will be added to local detailed plans every year. Targets have been set for the ownership/rental ratio and different modes of financing, and the plans must support the production of affordable housing. The city is committed to providing enough land to build at least 4,900 homes in both 2021 and 2022 and 5,600 each year from 2023 onwards. Approximately 50% of the new homes will be provided through infill construction in the city’s suburbs (including areas subject to suburban regeneration).

A well-functioning housing market plays a key role in responding to the challenges of growth. The aim is to build 6,000 homes annually in the first half of the City Council’s term (2017–2018) and 7,000 annually in the latter half (2019–2021). Helsinki is addressing the production of affordable rented housing in accordance with the AM Housing and Land Use Programme and actively scans for measures to control housing prices.

Helsinki caters for housing production by planning for 600,000–700,000 square meters of floor space annually and providing a sufficient number of sites for building. The city curbs the costs of construction and densifies the city structure by gradually moving – without risking its competitiveness and accessibility – towards an areal and market-driven parking system, starting in the new housing developments.

The rate of housing production has exceeded the targets towards the end of the strategic planning period. The target was 7,000 new homes in both 2019 and 2020, and 6,736 new homes were provided in 2019 and 7,280 in 2020.

The targets set for land use planning were exceeded in 2017–2020, and more than three million square metres of residential floor space were added to local detailed plans during the four-year period. Land availability has exceeded the rate of construction since 2013.

The city’s focus in 2019–2021 was on ensuring a healthy ownership/rental ratio: the goal was for 45% of new homes to be unregulated owner-occupied or rental dwellings, 30% to be right-of-occupancy homes and 25% to be social housing financed through the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland. The percentage of unregulated housing production has exceeded the target year after year. The volume of social housing production was on target in 2019 but has since fallen behind. The target for right-of-occupancy homes has also not been achieved.

One of the priorities is to develop and modernise the city in a balanced way so as to ensure the vitality and attractiveness of both new and old neighbourhoods. Other objectives include energy-efficient construction, a denser urban structure and good transport links. The city also wants to provide the right home for everyone at every stage of their life. Ensuring that there are enough homes in the city overall is important, but so is the availability of affordable options.

Efforts to streamline permit processes have helped the city to achieve its combined quantitative housing production targets.

The Urban Environment Committee decided at its meeting on 9 April 2019 that the principles of market-driven parking would be applied on a trial basis to housing developments in Nihti, Hernesaari and Hakaniemenranta.

The share of travel made on sustainable means of transport will be increased. All modes of transport will be developed and those kinds of transport that are key to business will be secured. Planning of the implementation of the city plan will start with the Vihdintie boulevard. Planning of the light rail line in that area will proceed to the decision phase during the Council’s term, and planning the Tuusulanväylä boulevard will move forward. The conditions for building a light rail line to Malmi will also be investigated. Development of the tramway network in central Helsinki and the implementation of the tramway plan for the Kalasatama area will proceed. Alongside the new housing areas being built in Helsinki, also infill construction will be enhanced.

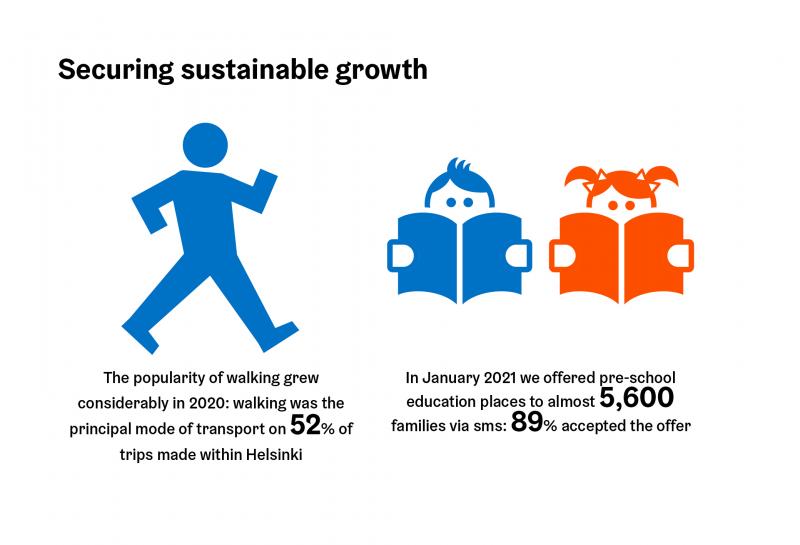

The popularity of walking grew considerably in 2020: walking was the principal mode of transport on 52% of trips made within Helsinki (compared to 36% in 2018). Public transport was the chosen mode of transport on 17% of trips (33% in 2018), a private car on 20% of trips (20% in 2018) and cycling on 11% of trips (11% in 2018).

The City Council approved a preliminary plan for the light rail line for the Vihdintie boulevard on 20 January 2021. The design principles for the boulevardisation of Vihdintie and Huopalahdentie were approved by the Committee on 5 June 2018. The Committee adopted a land use framework for the Vihdintie and Huopalahdentie area on 11 June 2019, and the City Council approved a preliminary plan for the West Helsinki tramway system on 20 January 2021.

The planning of the Tuusulanväylä boulevard and its public transport infrastructure has progressed during the Council term. The Urban Environment Committee approved the design principles on 18 December 2018. Work on a land use framework and traffic engineering are under way.

The drafting of a preliminary plan for the Viikki–Malmi light rail line began during the Council term.

The City Board adopted a rail transport development programme on 19 March 2018. The development of the tramway network in central Helsinki and the implementation of the tramway plan for the Kalasatama area are progressing. The City Council approved the implementation of the Kalasatama tramway plan on 13 June 2018. The Kalasatama tramway project is being implemented by two alliances, which have now progressed to the development stage. The first section of the Hernesaari tramway to Eiranranta opened to traffic in April 2021. The goal of turning the Jätkäsaari tramway into a three-line system has been promoted, for example, by launching the construction of the Atlantinsilta bridge. A line to Välimerenkatu was built in 2018, and the Atlantinkatu tramway opened to traffic in May 2021.

Accessibility analyses have been performed to study the densification of the city. These analyses measured the change in the percentage of people who rely on transport to get to their nearest shopping or commercial centre, relative to the change in the city’s total population. Measured in this way, the annual densification rate has varied between 0.9% and 1.7% during the strategic planning period.

The city has invested in infill construction and infrastructure around railway stations. Priority has been given to residential development in areas within 800 metres of train, underground or tramway stops and stations. At the end of September 2020, a total of 64.2% of Helsinki’s population lived in these areas.

We support every young person and prevent social exclusion

Together with relevant partners, Helsinki will launch an extensive and comprehensive project to find systemic solutions to the challenge of disaffected youth.

Young people who were not working or studying accounted for 5.5% at the end of 2018 (6.6% in 2016).

The social wellbeing of children and young people in different educational institutions and different year groups decreased between 2017 and 2019. Mood disorders affected a total of 13–17% of young people, signalling an increase of between 2.0 and 2.8 percentage points, excluding vocational school students. Children in years 4 and 5 had the fewest experiences of loneliness with 3.8%, but the rate was 12–13.6% among children in years 8 and 9, upper secondary school students and vocational school students. Feelings of loneliness have increased by between 0.6 and 2.6 percentage points. A national youth survey shows that young people’s satisfaction with life dropped to a record low in 2020. Although young people still score their quality of life as an 8 on the school grading scale, the figure is the lowest since records began in 1997. This phenomenon also needs to be kept under review in Helsinki.

Outreach and detached youth work have increased. Youth work priorities had to be urgently revised due to the coronavirus outbreak in March 2020 and the focus shifted to detached youth work and digital channels as well as personalised support.

Youth workers quickly became more competent in detached youth work, and digital channels helped to increase volumes. New tools were also introduced. These changes and the new competences are likely to affect the nature of youth work in the future as well.

The youth social inclusion project ‘Mukana’, which is one of the city’s strategic priorities, has brought different divisions of the city organisation together in an attempt to prevent social exclusion among young people. A systemic change has been started by addressing the root causes of exclusion, and the importance of prevention is now better understood. The divisions have developed a common system of identifying concerns and referring young people to sources of support with the help of, for example, an early intervention model for day care centres (‘Mitä kuuluu?’) and a social impact bond (SIB) service for families (‘Perheen mukana’). The city has developed new recreational opportunities for children and young people, focusing in particular on those who currently have no meaningful hobbies. Schools and other educational institutions have sought to systematically address absenteeism and bullying. Other actions taken include flexible teaching arrangements, supporting children with neuropsychological symptoms, intervening in racism and eradicating extremism.

The progress and impact of these actions are being measured with the help of performance, impact and effectiveness indicators. In some cases, a more extensive impact assessment has been performed. Each division of the city organisation has its own understanding of the mechanisms of exclusion, and it has not yet been possible to demonstrate impact. The effects of preventive action take several years to materialise. A baseline study on the risk of exclusion on an individual level has been conducted and a model developed for measuring impact in the future.

Successful prevention of exclusion requires the adoption of new approaches and mindsets in all of the city’s services. The coronavirus pandemic has only increased inequality as many services for children and young people have closed and schools have switched to distance teaching. Efforts to prevent exclusion must be redoubled once the pandemic eventually passes.

In Helsinki, the chain of public services for children and adolescents is strengthened at the basic level, namely in the local maternity and child health clinic, the day care centre, family counselling, school health care, school, youth work, health services and child protection.

A chain of services targeting mental health issues in children and adolescents has been modelled through extensive cooperation between the Social Services and Health Care Division, the Education Division, the Culture and Leisure Division and the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. Six workshops were run in the autumn of 2020, which involved documenting the service process and conceptualising the identification of mental health issues. A total of approximately 70 professionals representing the key services involved in the process contributed to the project. The new chain of services now covers everything from needs assessment to supporting the growth and development of children and from helping families with daily routines to ensuring that no one falls through the cracks. Key development priorities have been agreed and coordinators appointed for these actions for the years 2020 and 2021.

More student welfare officers have been recruited and their wages paid from the positive discrimination budget. Eight psychologists and social workers were hired for pre-schools in 2019. Cooperation between the child welfare staff of day care centres and schools can be vital in identifying and addressing children’s mental health issues at an earlier stage.

The city also has a mobile mental health team that specialises in identifying issues and referring those in need of support or treatment quickly to the right professionals. Mental health services for children and adolescents have also been promoted as part of the City of Helsinki’s Future Health and Social Services Centre project.

The objective of the City of Helsinki is that every child and adolescent has a hobby, that young people believe in Helsinki as their future home and that they are able to influence matters in Helsinki.

A total of 90.9% of children in years 4 and 5 had at least one hobby in 2019. The figure was 4.9 percentage points higher than during the previous year. Children in years 8 and 9 who had at least one hobby in 2019 accounted for 90.7%, which was 0.7 percentage points less than in 2017.

A national project called the Finnish Model of Hobbies has been launched with special funding from the Ministry of Education and Culture. The model is designed to give every child the opportunity to engage in a meaningful extracurricular activity that they enjoy. The model is expected to still receive funding during the next Council term.

To create opportunities for equality to be realized, the city ensures that its facilities are easy and safe to use for educational, civic participation and cultural activities.

The Varaamo booking system has been improved to make public spaces more easily accessible to residents. A new administrative model was adopted in 2020 and a steering group appointed by the City Manager to coordinate the system. Approximately 130 different facilities can currently be booked through Varaamo. However, the system only includes a fraction of the facilities and resources that could be suitable for residents at the moment. More facilities are being added all the time, and the plan is to retire overlapping systems in the future. Work is also under way to make it possible to book facilities on a regular basis through the system.

The Oodi central library and the Bunkkeri sports facilities in Jätkäsaari will be carried out in a way that does not jeopardize local services.

Oodi opened without jeopardising local libraries and added more than three million new library customers. Oodi also won numerous international awards and nominations during its first years of operation.

The city has continued to pursue the Bunkkeri sports facility project despite pending appeals. Helsinki Administrative Court dismissed an appeal relating to the sale of the land, but the case is still before the Supreme Administrative Court. The execution of the project cannot begin until a final verdict in the case has been delivered. The city has revised the investment programme to allow for the land to be leased instead.

An international, living and captivating Helsinki of events

To increase Helsinki’s international appeal, a deliberate internationalization of the city is required. Employment-based immigration and its share of total immigration are encouraged and increased.

Employment-based immigration was promoted through, for example, campaigns aimed at attracting skilled professionals and special measures designed to support the settlement of their spouses in Helsinki and finding a job in the area (e.g. International House Helsinki and a programme for spouses).

The City of Helsinki’s integration programme for the years 2017–2021 (‘Helsinki – a City for Everyone’) was finalised in the spring of 2018. The city has strived to make settlement easier by drawing up a programme for the development of English-language services, which sets out ways to improve the standard of English-language communication and services in the city.

The capacity for English-language education and early childhood education will be doubled. The language skills of Helsinki citizens are to be diversified by increasing language immersion and language-oriented training and education. In Helsinki, tuition in the first foreign or second national language will start already during the first school year. The tuition of Chinese is being expanded. Together with Scandinavian networks, a common concept, Nordiska skolan (the Nordic school), is being created in Helsinki.

Language tuition has been increased in Helsinki. Every year, 6,000 children start learning their first foreign language or the second national language in year 1. The number of places in English classes has been doubled. More opportunities for learning Chinese are now provided both as part of basic education and in upper secondary schools. Children now have the option to begin learning their second foreign language in year 3. Helsinki Vocational College and Adult Institute has started to offer tuition in English. Teaching staff in all forms of education have received additional language training.

The Baana cycle and pedestrian corridor and Töölönlahti area is being turned into a high-quality and internationally known culture and leisure cluster. The possibility of making the Suvilahti area an internationally salient venue for large events is investigated. The developing network of museums will be further strengthened wherever possible. Helsinki will lighten its permit and organization procedures to make it easier to organize various kinds of events.

A report on the new organisation of Helsinki Art Museum came out in October 2019. Based on the report, the current plan is to relocate the museum from the Tennispalatsi cultural centre to the old gasometers in Suvilahti. An architectural competition on the development of Suvilahti into an event complex was run by Suvilahti Event Hub Oy, the Finnish Association of Architects and the City of Helsinki in 2020. Work on the local detailed plan has begun with the winner of the competition. The area will also include an open-air arena, the planning of which has been outsourced to a consultancy firm. The city has invested in making the area more suited to hosting large public events.

A programme for the decommissioning of the Hanasaari power plant was finalised at the end of 2020. Planning of the area’s function after the plant has been decommissioned (2024) has begun, and the provisional idea is to turn the plant into a cultural centre and leisure complex. A needs assessment is being conducted at the moment.

An attractive city centre is a calling card and a must for Helsinki. The central business district of Helsinki is an attractive venue for commercial services, events, leisure and civic participation.

The number of people visiting or spending time in the city centre dropped by 40.8% from 7.6 million (in 2019) to 4.5 million (in 2020) due to the coronavirus outbreak.

An outdoor dining area was set up in the Senate Square during the pandemic, and a similar project is due to go ahead in Kasarmitori square in the summer of 2021. The Helsinki Events Foundation and Helsinki Festival have also contributed to the city’s events calendar. The city helped restaurateurs in the summers of 2020 and 2021 by simplifying the process of applying for an outdoor licence.

The city is investigating the possibilities for a substantial expansion of the central pedestrian zone in order to further improve the atmosphere and functionality of the central business district, and for building an underground distributor road that would reduce traffic through the city centre as well as heavy transports to the harbours.

The investigation into the possibilities of extending the pedestrian zone in the city centre and building an underground distributor road did not progress as planned, and instead the City Board decided to continue the planning of the pedestrian zone but discontinue the planning of the underground distributor road.

The City Council adopted a resolution on the reorganisation of the Port of Helsinki and the principles of land use in the South Harbour, Katajanokka Harbour and West Harbour on 3 February 2021. The majority of port operations will be based in Katajanokka Harbour and West Harbour in the future, and a tunnel will be built to connect the West Harbour to the Western Highway. The goal is to turn the heart of the city and the South Harbour into a multifaceted, atmospheric and attractive urban seaside environment.

The land use objective for the South Harbour is to incorporate more of the area into an active, living pedestrianised zone. This requires the ability to ignore the reservations made in existing land use plans for port infrastructure as well as the effects of vehicular traffic in and out of the port. The planning area has been extended to also cover the southern and northern esplanades, the options for which will need to be analysed separately. Decisions will be made based on the analysis in the autumn of 2021. The next stages of the pedestrianisation project will also be agreed at that time. The vision for the city centre adopted by the City Board on 25 January 2021 also advocates pedestrianisation.

The waterfront between the Olympia Terminal and the Market Square is developed into a functional whole supporting the vitality of the city centre.

The city is organising a quality and concept competition seeking an extremely ambitious yet practical way to approach land use planning and the future development of the area. The competition was launched in the spring of 2021 and is due to be completed before the end of 2022. Construction in the area could begin in 2025. The planning area also includes a reservation for the new museum of architecture and design, for which a separate architectural competition will be organised later.